if only i could

dream of roses

flower study

The following projects stem from several different sources, the first of which is a personal obsession with flowers and their forms. This obsession arises from the sublime qualities of the blossom — a form so delicate and fragile, tangible only for a fleeting moment. It is a centralized composition that presents the illusion of simplicity, yet upon closer inspection reveals layers of complexity: from the subtle gradation of hue, even in the purest white bloom, to the intricacy of its structural organization.

From the simple act of planting a seed emerges a form that radiates outward, petals unfolding into a composition that suggests radial symmetry. Yet within this order lies variation: each petal diverges slightly in orientation, curvature, and proportion, ensuring that no two are ever truly alike. This balance of repetition and differentiation reflects principles of rhythm and variation, generating a dynamic system within an apparently stable framework.

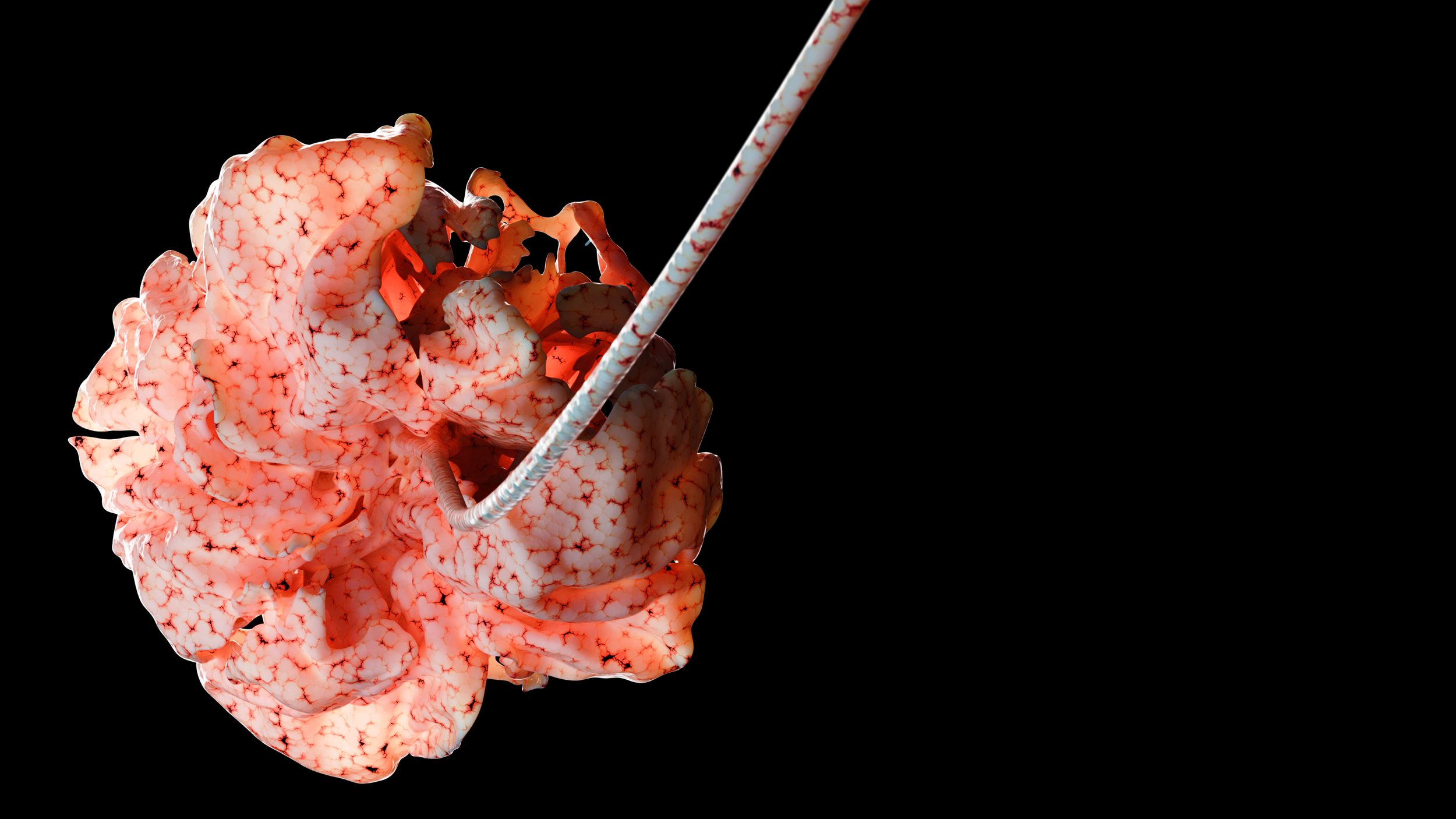

The second source is an artwork titled Not a Rose by Heide Hatry. While Hatry initially presents her work as flower photography — adopting the techniques and aesthetics of botanical representation — the essence of her practice is revealed only upon closer examination. Hatry manufactures flowers not from plant material, but from the sexual organs and tissues of animals. Through acts akin to butchering or dissection, she collects various animal parts and arranges them into forms that mimic the radial compositions of blossoms. The resulting constructions are placed in natural contexts — a garden, for example — and photographed, with only the photographic image presented as the final artwork.

In works such as 28 Linguae, Saeta Cervorum, Sanguis Coagulatus, Hatry employs tongues, deer hair, and coagulated blood to construct her hybrid “flowers.” The materiality of flesh introduces unsettling associations, yet at the same time echoes the natural effects found in true blossoms: subtle gradations of hue, delicate textures, and fragile surfaces reminiscent of petals. In this way, Hatry’s work both imitates and disrupts the aesthetics of the flower, questioning the boundary between beauty and repulsion, nature and artifice.

While flowers are themselves the sexual organs of nature, Hatry’s works complicate this notion by replacing the botanical with the anatomical. She does not merely mimic the flower, but substitutes its generative function with another, sourcing sexuality from flesh rather than flora. In doing so, her practice exposes a primal equivalence between the reproductive structures of plants and animals, suggesting that without the flower, the flesh — as a metaphor for desire, fertility, and mortality — could not be fully understood.

In my own approach, I investigate the formal complexity of floral structures — not to reproduce flowers, but to understand the mechanisms through which they come into being. My work follows basic formal principles: beginning with a single unit, which is then distorted to create variation, and arranged into a circular radial array. Each of these produced “flowers” does not aim to mimic natural forms directly, but rather to generate a tension between what is perceived and what is expected — between the experience of the present image and the residual memory of the natural blossom. My goal is not confirmation but doubt: to destabilize recognition and extend the moment of uncertainty in the act of viewing.

Each unit used to construct these forms emerges from an investigation into what I call the “digital blob”: abstract digital models that, when isolated, carry no intrinsic meaning. Just as Hatry employs discarded animal parts — remnants that are overlooked or deemed unusable — my work reclaims disregarded digital forms. Though created with intention, these forms initially lack purpose; only through their arrangement into floral structures do they acquire new significance.

While the works are digital sculptures, the materials assigned to them in rendering are carefully chosen to re-examine Hatry’s use of flesh. They echo the tonalities and gradients of natural petals, blurring the boundary between the artificial and the organic. The renderings aim to prolong the perceptual hesitation of the viewer, extending the window of contemplation and heightening the tension between recognition and doubt.

Conclusion

Flowers, whether natural, fabricated from flesh, or digitally rendered, reveal themselves as sites of tension and transformation. They embody both simplicity and complexity: the act of planting a seed produces a form that, over time, grows into a layered structure of rhythm, geometry, and variation. In this sense, the flower becomes more than a natural ornament — it becomes a system of form, an exploration of how material, symmetry, and difference generate recognition and estrangement at once.

At the same time, flowers remind us that beauty and repulsion often share the same structure. To experience them socially or domestically, the flower must be cut — removed from its living system — and suspended in a vase to prolong its presence. This gesture is paradoxical: in order to extend the act of viewing, the flower must first be killed. Its delicacy and vibrancy are preserved only temporarily, elongating the experience of sight and touch just a little longer. In this contradiction — between life and death, simplicity and complexity, attraction and decay .

Half a dozen

Flower one

Flower two

Flower three